By Leslie Madsen-Brooks

This series of three posts draws on research I originally undertook in 2001 and 2002. It is a distillation of a much longer paper; if you’re interested in a literature review, a description of my research methods, more details from interviews, and deeper background on the topic, visit Museum Blogging. For the purposes of the paper I was writing, I interviewed many science center employees, but many spoke off the record; accordingly, I have removed all interviewees’ names, and frequently any identifying information about their institutions, from this post. This research was supported in part by a grant from the Consortium for Women and Research at the University of California, Davis.

Between 2001 and 2004, when I was working as an educator, exhibition developer, or occasional evaluator for Explorit Science Center in Davis, California, I often found myself standing in front of classrooms of elementary school children. Chances were about even that one of the girls would say to me, “You’re pretty” or “I like your hair.” Even some of their thank-you notes to me said such things, scrawled there at the end after “I learned that I will be 5 feet 6 inches tall.” Boys wrote things like, “I learned dinosaurs poop and it turns into a rock.” I wish the girls would, to a person, write about coprolites and gastroliths, about hissing roaches and the mites that swarm over giant millipedes’ legs. In my experience, girls do seem interested in science, but the things they focus on and remember are much more person-oriented and bodily than are boys’ observations.

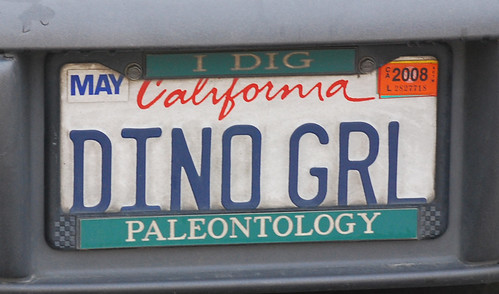

Photo by Rhys, and used under a Creative Commons license

When I mentioned my frustration with girls and the lack of opportunities available specifically to girls to a staff member at Explorit, she sighed and lamented that many of the center’s science-centered birthday parties have “boy” themes, like “Rockin’ the Earth” or “Dinosaurs and Reptiles.” She suggested developing a birthday party focused on kitchen science. And indeed, “Kitchen Chemistry” is one of the science center’s most popular special parent-child classes. But must girls be left stirring in the kitchen, while the boys are in the multipurpose room making balloon rockets?

While many of the girls in the classes and birthday parties I oversaw seemed truly engaged with the hands-on science presented in the lessons, I wondered how many of them would nurture that interest through their teen years and into college. Since K-16 schools too frequently fail to inspire girls and young women to pursue science, I want to see if informal science learning might be more successful. In particular, I want to focus on the opportunities available to girls and young women at museums and science centers.

Over the past three decades, there has been incredible growth in both the quantity and quality of science museums and science centers throughout the United States, and especially in California. During the same time period, it has become evident that traditional schooling systems have not been entirely successful in engaging young women in science. While girls are enrolling in some advanced science classes at the same rates as their male counterparts, they still drop out of the “science pipeline.” I undertook this project to discover what informal science learning activities science centers are developing to ensure that girls are made aware of and encouraged to pursue the incredible lifetime opportunities available to those who choose scientific careers. This project explores, then, the informal science learning experiences available throughout childhood and adolescence and their success in sparking young women’s desires to pursue scientific careers.

Background

Science studies theorist Helen Longino emphasizes the necessity of rethinking how science is practiced and who counts as a practitioner: “We cannot restrict ourselves simply to the elimination of bias, but must expand our scope to include the detection of limiting and interpretive frameworks and the finding or construction of more appropriate frameworks.” She suggests that to bring girls and women into science, we must change not just the content of science, but its entire context. In changing the context of science, Longino explains, we are trying to bring it into line with “the values and commitments we express in the rest of our lives” (1987, 60). In short, if a community values women and the health of all its members, then it must encourage its resident women to participate in science. But what institutions in a community can provide the framework needed to sustain girls’ and young women’s interests in science?

The answer may be simple. Many metropolitan areas boast an impressive assortment of museums, science centers, zoos, aquaria, and botanical gardens. These spaces are critical locations for not only public learning, but also public dialogue on a broad spectrum of issues. Although much scholarly work has sought to elucidate the sources of social controversies in history and art museums and recommend ways to solve tensions within and between the communities museums serve, significantly less scholarly attention has been paid to science centers and how these museums’ exhibits and outreach programs affect girls’ and women’s perception of, and participation in, science. This is unfortunate, for the research that does exist has uncovered gendered patterns of scientific learning that warrant greater attention. Too see a summary of that research, visit the longer version of this essay.

California’s diverse urban communities pose additional challenges and opportunities for educational outreach. How does a science museum ensure its exhibits speak to everyone, regardless of ethnicity, class, or gender? In solving such quandaries, feminist science studies takes a decidedly antiracist stance, and seeks to include as many people as possible in conversations about the role of science in multicultural communities. Some theorists believe that thoughtfully solving “the woman problem” will in large part take care of “the race problem” as well. As Sandra Harding explains in Whose Science? Whose Knowledge?,

Women need sciences and technologies that are for women and that are for women in every class, race, and culture. Feminists (male and female) want to close the gender gap in scientific and technological literacy, to invent modes of thought and learn the existing techniques and skills that will enable women to get more control over the conditions of their lives. Such sciences can and must benefit men, too—especially those marginalized by racism, imperialism, and class exploitation. (1991, 5)

The stakes are high. Because they have such a close connection to the public—and often to public schools—museums can serve as excellent launching grounds for such a project, sometimes for no other reason than these institutions have excellent access to young people, whose excitement about and perceptions of scientific endeavors remain malleable. These students have not yet been indoctrinated into the androcentric notions that pervade much of Western science—notions that serve to oppress vast portions of the world’s population through exclusion from participation in science or policies that endanger the health and lives of specific communities.

We must assess where museums stand now, and what steps they might take to increase the participation of women, and especially women of color, who remain underrepresented in nearly all branches of the natural and physical sciences.

To continue reading on to Part II click here.

Leslie Madsen-Brooks is an adjunct professor of museum studies at John F. Kennedy University and a consultant on issues of education and professional development. If you liked this post, check out her blog Museum Blogging or contact Leslie directly: leslie -at- museumblogging -dot- com. You can also sign up for her occasional newsletter on museum professional development.

Comments

Leslie, this is intense and necessary. This kind of investigation into gender-based interpretation and presentation can only help us better the work we all do in every kind of museum. My mother was a great scientist, dedicated to mentoring other young women to enter the field. I can’t help but think of her and how significant this kind of exploration is for museum professionals dedicated to making the world better through the work they do. Looking forward to watching the next two installments roll out. Thank you!

Thanks, James! It's a topic that's close to my heart.

Add new comment