By: Sarah Asper-Smith

In November, I traveled to Nome for the first time. I have been surrounded by incredible beauty my whole life—I grew up in the coastal rainforest of southeast Alaska, and stare out my window at tall mountains and lush, green forests. But the flight to Nome was breathtaking. Every region of Alaska carries its own beauty, different from the others. My nose was pressed to the glass for the entire flight from Anchorage, hoping that my iPhone would capture the grandness of this amazing place.

In November, I traveled to Nome for the first time. I have been surrounded by incredible beauty my whole life—I grew up in the coastal rainforest of southeast Alaska, and stare out my window at tall mountains and lush, green forests. But the flight to Nome was breathtaking. Every region of Alaska carries its own beauty, different from the others. My nose was pressed to the glass for the entire flight from Anchorage, hoping that my iPhone would capture the grandness of this amazing place.

I have worked as a designer since high school, and started museum exhibition design in 2004, when I approached Bob Banghart, an accomplished exhibit designer, about his profession. He invited me along on a trip to Barrow at the very northern part of the state, and I have been hooked ever since. After working with the Juneau City Museum on subjects ranging from basketball to motorcycles, I decided to apply to the University of the Arts in Philadelphia for their MFA program in Museum Exhibition Planning and Design. It proved to be everything I dreamed of, plus more. Being there intensified my desire to return to Alaska and work with small museums all over the state. Not only would I be able to help these communities tell their stories, but I could meet the extraordinary people in my extended Alaskan community!

Nove mber in Nome is of what you imagine when thinking of frozen Alaskan winters. It is not advisable to go out walking for long, but there was enough light that first day to photograph the frozen Bering Sea. Nome, population 3,600, formed as a city because of gold mining and at one time had a population of 20,000. Nome is a hub community for the small Native villages in the Bering Strait region.

mber in Nome is of what you imagine when thinking of frozen Alaskan winters. It is not advisable to go out walking for long, but there was enough light that first day to photograph the frozen Bering Sea. Nome, population 3,600, formed as a city because of gold mining and at one time had a population of 20,000. Nome is a hub community for the small Native villages in the Bering Strait region.

The next day I presented to the Cultural Advisory Committee of the Beringia Center. The Beringia Center operates under the direction of Kawerak, Inc., a tribal organization that serves the Native communities of Bering Strait. And the Beringia Center aims to serve the fifteen different rural communities as a central hub of art, culture, history and science. There are plans for the development of a building in Nome, but the Beringia Center also wants to be a museum without walls, bringing exhibits and activities to the villages of the region that it serves.

That’s where I came in. My task was to develop the first of these exhibits. The Beringia Center has a collection of ancient harpoons in storage, and we wanted to develop a traveling exhibit based on these small artifacts. My first step was to meet with the Cultural Advisory Committee; to learn about harpoons and ask them their ideas about the kind of exhibit they would like to see. The Cultural Advisory Committee consists of a representative from each of the fifteen villages. Elders and community leaders sat around the table, ready to offer their knowledge and expertise. While the meeting took place in English, it was peppered with words and phrases from each of the Alaska Native languages represented: Iñupiaq, Yupik, and Siberian Yupik. The group patiently answered questions that I had about the harpoons--how did the toggling harpoons even work?  They explained how the blade would fit into the tip of the harpoon head; after it penetrated the skin, the harpoon head would toggle and become stuck in the animal. In this way, the hunter could pull the seal or walrus out of the water, and the animal wouldn’t sink out of his grasp. Merlin Koonooka, an Elder from St. Lawrence Island told me: “we never hesitate to improve our equipment. We adopt to modern ways very naturally.” I also learned that traditionally, a young hunter’s first catch is given to an Elder in the village. It is a sign of respect, and also ensures luck for the hunter. I thought about how lucky I was to be sitting in this room with kind people willing to share their ancient knowledge.

They explained how the blade would fit into the tip of the harpoon head; after it penetrated the skin, the harpoon head would toggle and become stuck in the animal. In this way, the hunter could pull the seal or walrus out of the water, and the animal wouldn’t sink out of his grasp. Merlin Koonooka, an Elder from St. Lawrence Island told me: “we never hesitate to improve our equipment. We adopt to modern ways very naturally.” I also learned that traditionally, a young hunter’s first catch is given to an Elder in the village. It is a sign of respect, and also ensures luck for the hunter. I thought about how lucky I was to be sitting in this room with kind people willing to share their ancient knowledge.

I left feeling inspired, knowing that this intersection of adaptation and tradition is a powerful place to be. I also knew that it would not be appropriate for me to approach this project as an expert in harpoons--I’m not! But I can ask questions, I can provide a forum for discussion and sharing, and I wanted to learn as much as possible from Elders and community leaders who know more than I.

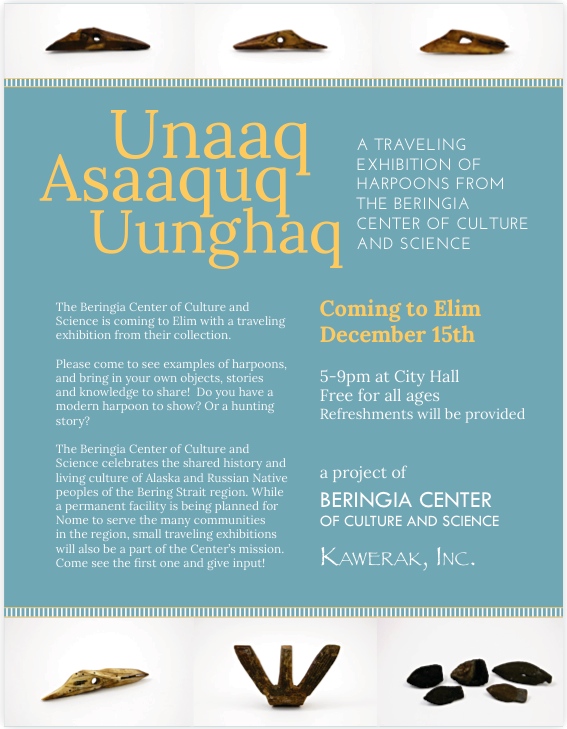

It was determined that the village of Elim would be the first exhibit location. And it had to be done in one month! I worked closely with Amy Russell, the executive director of the Beringia Center and others at Kawerak to develop an exhibit that would travel the ancient artifacts to Elim for a one-day exhibition. After consulting with language speakers, the exhibit title became Unaaq Asaaquq Uunghag, the words for harpoon in the three Alaska Native languages of the Bering Strait region.

It was determined that the village of Elim would be the first exhibit location. And it had to be done in one month! I worked closely with Amy Russell, the executive director of the Beringia Center and others at Kawerak to develop an exhibit that would travel the ancient artifacts to Elim for a one-day exhibition. After consulting with language speakers, the exhibit title became Unaaq Asaaquq Uunghag, the words for harpoon in the three Alaska Native languages of the Bering Strait region.

I returned to Juneau to work on the exhibit, ordering necessary materials and planning a case that could transport the objects on a small plane. While I was in soggy Southeast, a powerful winter storm blew water from the Bering Sea up to the base of buildings in Nome and made national news. Returning to the community, I discovered that an already somewhat isolated and inaccessible place had become even more so. Everything in Alaska depends on weather. Unfortunately, this meant that many of the materials we had ordered for the exhibit were stuck en route in Anchorage or Juneau, and we had to adapt and make do. It seemed fitting, given the theme of the exhibit.

We traveled to Elim, population 300, a day early because we were worried about stormy weather delaying flights. The plane took 3 passengers: myself, Amy and a man who got off in Golovin on the way to Elim. We were met by a snowmachine pulling a sled, and so our exhibit traveled by car, plane and snowmobile to reach its destination!

We traveled to Elim, population 300, a day early because we were worried about stormy weather delaying flights. The plane took 3 passengers: myself, Amy and a man who got off in Golovin on the way to Elim. We were met by a snowmachine pulling a sled, and so our exhibit traveled by car, plane and snowmobile to reach its destination!

Unaaq Asaaquq Uunghaq was held in the Elim City Hall from 5–9pm on December 15th. The exhibit contained a display of 7 harpoon heads, 2 harpoon blades and 1 counterbalance from the Beringia Center’s collection. Labels accompanying the artifacts described harpoon technology and told stories of hunting. A slideshow of historic and contemporary images as well as seal hunting and toggling harpoon simulation video clips played on a wall. We asked questions of the visitors, and displayed themed exhibit panels.

blades and 1 counterbalance from the Beringia Center’s collection. Labels accompanying the artifacts described harpoon technology and told stories of hunting. A slideshow of historic and contemporary images as well as seal hunting and toggling harpoon simulation video clips played on a wall. We asked questions of the visitors, and displayed themed exhibit panels.

Visitors had been asked to bring in their own artifacts to share, two did so. It was thrilling to see contemporary harpoons alongside the ancient artifacts, and listen to hunters and Elders discuss the way the tools worked.

I designed eight different dialogue panels to ask questions of the visitors, and provided big sheets of paper and markers. Asking the community what they knew was very important to the project, as we wanted the community to feel ownership of the exhibit. Integral to this process are the stories of the community. Many visitors responded to these questions with personal answers, and I overheard visitors talking about the questions with their friends. The questions started some conversations, and the answers provided insight into Elim life. Harpoons and hunting segued nicely into a topic that everyone loves to talk about. “What is your favorite food that is hunted or gathered or caught?” The answers were written in different colors all over the paper:

I designed eight different dialogue panels to ask questions of the visitors, and provided big sheets of paper and markers. Asking the community what they knew was very important to the project, as we wanted the community to feel ownership of the exhibit. Integral to this process are the stories of the community. Many visitors responded to these questions with personal answers, and I overheard visitors talking about the questions with their friends. The questions started some conversations, and the answers provided insight into Elim life. Harpoons and hunting segued nicely into a topic that everyone loves to talk about. “What is your favorite food that is hunted or gathered or caught?” The answers were written in different colors all over the paper:

Crab, rabbit, snow geese, moose, caribou

Mangtuk, beluga whale (maktak)

Half dried fish in whale oil

Black berries mixed with salmonberries

Pickled beluga whale

Agutak (a traditional dish of seal oil and berries)

Aged beluga whale

Aged seal flippers

Geese

Oogruk (bearded seal) and seal blubber, walrus meat

Panaaluk (dried oogruk meat)

We received 65 visitors during our exhibit, in addition to over 50 students that Amy spoke with during school hours. We knew it had been a success when we heard a visitor ask: When are you coming back?

Sarah Asper-Smith has the best job in the world. She is a museum exhibition and graphic designer in Juneau, Alaska, but gets to travel all over the state meeting interesting people. She was a Wanda Chin fellowship recipient in 2010, while she attended graduate school at the University of the Arts. She can be reached via her website: exhibitAK.com

Sarah Asper-Smith has the best job in the world. She is a museum exhibition and graphic designer in Juneau, Alaska, but gets to travel all over the state meeting interesting people. She was a Wanda Chin fellowship recipient in 2010, while she attended graduate school at the University of the Arts. She can be reached via her website: exhibitAK.com

Add new comment