By Renee Montgomery

Recently, the international media reported that Colombian officials raided the Pablo Escobar Museum in Medellin, closing it down with a sign on door. Up to his 1993 death, drug lord Escobar and his Medellin cartel had supplied 80% of the U.S. cocaine market, making him the wealthiest criminal in history with a $30B estate. All totaled the Cartel was responsible for an estimated 4,000 deaths, including 600 police, half the supreme court, and the passengers of a downed plane believed to be carrying a pro-extradition presidential candidate. When finally cornered a year and a half after escaping prison, Escobar either was shot, or as his fan base would like to believe, committed suicide. Escobar's earlier offer to personally offset the national debt in exchange for immunity hadn’t been accepted but "Pablito" nevertheless achieved Robin Hood status by funding housing and sport facilities for the city's poorest. 25,000 attended his funeral, followed by t-shirts, bumper stickers, books, a National Geographic documentary, a Netflix series, a movie... well, once Penelope Cruz gets involved, you know you're a legend.

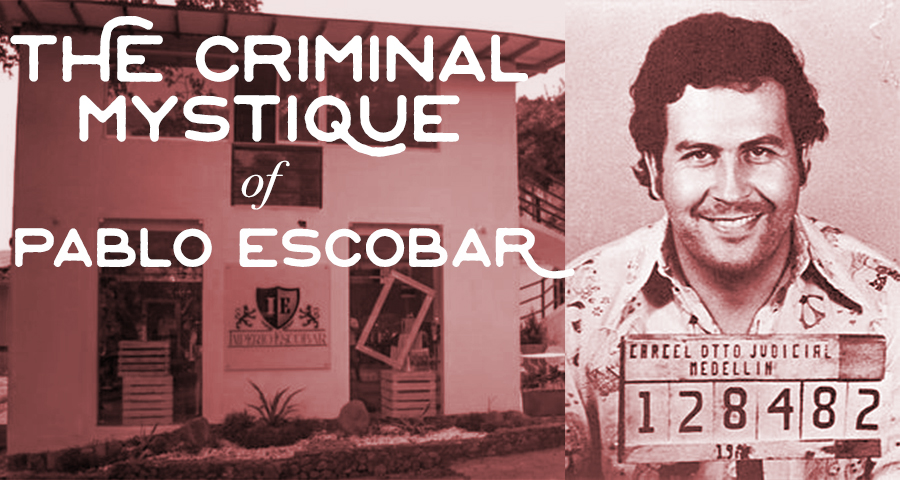

The Pablo Escobar Museum in Medellin, Colombia

On September 19th, authorities pointed out that Pablo's little brother Roberto, the museum owner/operator, had failed to obtain the proper license with the Ministry of Trade, Industry and Tourism. The Escobar Museum, exhibiting the drug baron’s expensive toys, is just one stop on the growing number of 'narco-tours' popping up in Medellin (NPR reported a total of 15 earlier this year). Anxious to clean up the country's image as the murder capital of the world (The Real Housewives of NY were entertained in Colombia's Cartagena last season for gosh sake!) the government struggles mightily with the insidious Escobar hero-worship industry. "There is a temporary suspension of the activities of this business in Medellin, dedicated to promoting the life of one of the saddest bandits, of those who have done the most damage to this city," the Medellin Security Chief described the museum shut-down. "As if it that were not enough this establishment also did not comply with the regulations." The Mayor stated, "We have to tell the story, not the mobsters."

Hundreds of museums across the U.S. bear testament to the public's fascination with crime and darkness: the Mob Museum, museums dedicated to the memory of Bonnie and Clyde, Jesse James, and, especially in the West, Billy the Kid, Butch Cassidy: all not nice people. An exhibition of the state's most notorious offenders is currently showing in conservative Kansas. Such museums strive for non-glorified portrayals but the bad guys' brazen stories inevitably overshadow the silent victims in our collective consciousness (or conscience). Although Colombian officials hope the narco-tours will present a balanced account of the drug czar's swath of destruction, the guides providing first-hand accounts of Escobar's mystique, like brother Roberto, are most popular. The Romance of the Outlaw burns brightly.

Pablo Escobar's jet ski on display at the Pablo Escobar Museum

People much smarter than me have written about our impulse to rubberneck at horrendous brutality—how it must certainly reflect some deep-seated Darwinian survival instinct—our compulsion to examine the deviant minority probably being designed to reinforce acceptable social norms? Or perhaps we’re simply wound so tightly by society's constraints, we can't help but cheer on the elite offenders who've managed to royally elude the rules? Whatever primitive hard-wiring may be controlling our fascination with evil, it's the museum's role to explain ourselves to ourselves, especially our most base selves, using the tangible relics of our past, whether they be bullet-ridden windshields or jet skis.

Reported from Fox News to the BBC to the India Times, rather than slowing down the little Escobar museum, the authorities' bureaucratic hassling of Roberto just wrote the next chapter. Stay tuned for the grand reopening. Some human sagas are just too gripping to look away.

Renee Montgomery served as a senior manager at LACMA for 35 years dealing with exhibitions and collections. She currently straddles L.A. and Tulsa Oklahoma where she is an art educator.

Add new comment