By Ferdinando Adorno, Principal Architect, Ferdinando Adorno Architecture

Museums all over the world are increasingly recognising their obligation and the opportunity to consider climate change as a key issue of their commitment towards society. If museums plan to be in existance for forever, they have to take impacts of climate change into consideration. Today their roles are far more complex than simply preserving and interpreting cultural artifacts. It is critical that the museum sector started recognising their role in improving society by working on contemporary issues and using their expertise to make a positive difference to their communities. But in a period of of post-truth politics, alternative facts and revisionism, how museums, as trusted institutions, how can they commit to develop public opinion and political action around climate change?

The terms of this challenge have been well outlined by Philip Kennicott in June 2017 in the Washington Post. Kennicott begins describing the "Imaginary view of the Grand Galerie in the Louvre in Ruins" painted by Hubert Robert in 1796:

"The French artist shows the imaginary decay of what was then a perfectly sound building. By including in the view an image of the Apollo Belvedere (one of the greatest relics of antiquity) and a bust of Raphael (the beloved master of the Renaissance) the painting becomes a conversation piece about the transmission and resilience of culture through the ages. In the 18th century, depicting the Louvre in ruins wasn’t a dark fantasy of some coming holocaust. Rather, it aligned your world with the values of Greece and the splendors of Rome. But it also spoke to art’s solacing power in the face of our own mortality. At the heart of every aesthetic experience is the hope that someone, in the future, will experience the same thing, and that some part of our living consciousness, made manifest by a painting, symphony or great poem, will be replicated and repeated by other beings whom we will never know. That won’t happen if the planet dies."

Image: Hubert Robert, “Imaginary View of the Grande Galerie in the Louvre in Ruins” (1796)

The atmospheric concentration of carbon dioxide is one of the key parameters to understand the state of wealth of our Planet. This indicator correlates with Earth's surface temperature, giving an idea about the impact of human activities on the future global warming. In 2016, for the first time in millions of years, we passed the threshold of 400 parts per million of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere. At this pace, we'll hit 450 ppm within a few decades, anticipating a warming of two degrees Celsius above pre-industrial temperatures. Effects of this change in climate are already disastrous in the form of rising seas, storms, wildfires and extreme weather of all kinds, hitting primarily the poorest areas of the World. Further rises in temperature will make these events worse and increasingly frequent which will make life on Earth difficult, if not impossible for most of the life forms including humans. The safe level of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere is 350 parts per million. It will take centuries to back this level. The only way to get there is to immediately transition the global economy away from fossil fuels and towards clean energy technology and reducing carbon emissions.

We are all contributing to this negative trend and we are all in the system, but we are not equally responsible. Indeed, as Naomi Klein pointed out: climate change is not about science and politics, is about social justice and we are told that we can’t respond to this crisis. "Sometimes we are told that we are the frog in the boiling water. The problem is that climate change is unfolding slowly. If we have had a sudden shock we would do like the frog put in the boiling water, we would jump." To the contrary, we are placidly placed in a pot of tepid water, gradually heating up, allowing ourselves to be boiled over low heat. And I agree with Naomi Klein when she says that’s not accurate: "what we actually see is the we keep on trying to jump but then something happens and something puts the lid back on the pot. And that lid is the power of the fossil fuel, lobbies of the fossil fuels interested that are gaining so much from this hyper-concentrated economic model" (Klein, 2015).

On the one hand climate deniers use uncertainty to justify inaction. On the other hand scientists have trouble, for instance, turning their broad global forecasts into specific predictions for a given locality. But the real unknown is our behaviour and how much carbon we are going to pump into the air.

When decisions are urgent, stakes are high, facts are uncertain, and the dispute shifts on values then climate change becomes a cultural problem. Culture intervenes in every dimension of society's response to global climate change (Adger, 2013). Culture is embedded in the modes of production, consumption, lifestyles and social organization that give rise to the emissions of greenhouse gases. Culture shapes values of individuals and communities and their capacity to adjust to risks, either in reaction or in anticipation. Because of this museums, as widely respected, trusted, and open institutions, can play an important role in disseminating a culture of climate change, aiming at raising awareness and developing responses from local to global scale. The intensity of this message depends on the specific characteristics of each museum: typology, size, collection and funding support.

Art museums can play a special role as creators of aesthetic experiences, spaces for critical reflections and institutions for collective and individual cultivation. For this reason, they are excellent laboratories of experimentation and innovative practices where art and science are inextricably linked and reinforce one another's action. Some examples arise from the line of storms which last year hit the Gulf Coast and Caribbean, causing catastrophic damages.

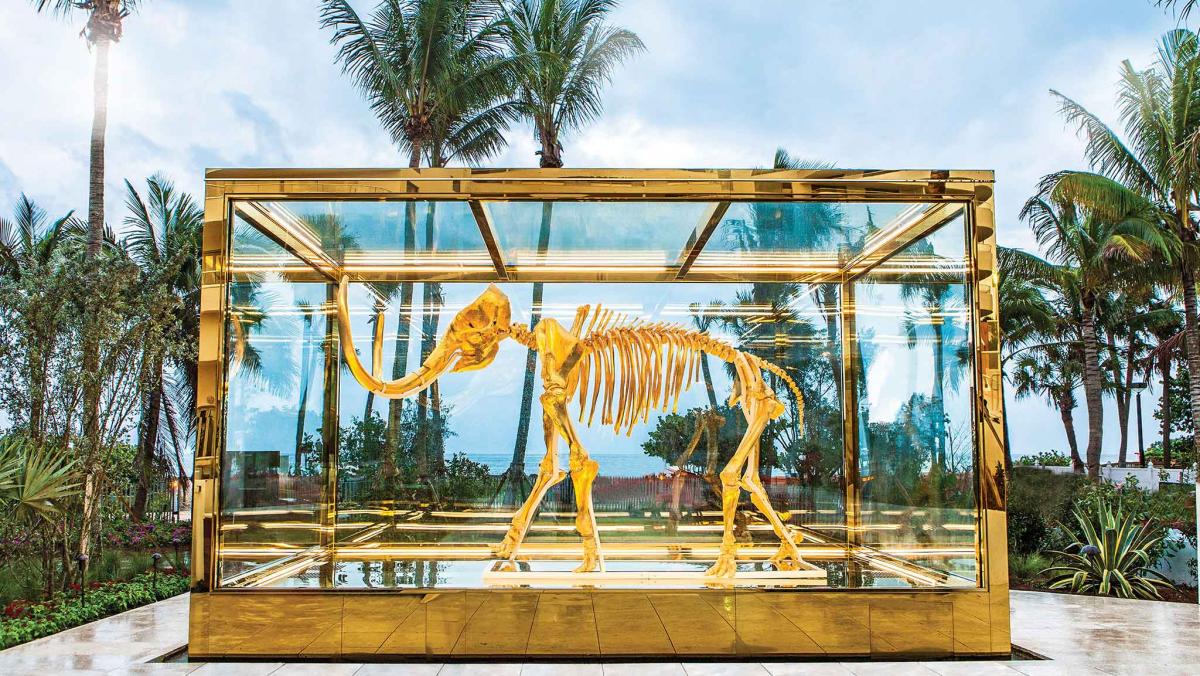

In Miami Hurricane Irma, ranked as one of the most powerful hurricanes ever documented in the Atlantic, significatively threatened the city and its inhabitants. According to the National Oceanic & Atmospheric Administration, the city has a 48% chance of experiencing the impacts of a tropical storm or hurricane every year. In Miami Hurricane Irma significatively threatened the city and its inhabitants. According to the National Oceanic & Atmospheric Administration, the city has a 48% chance of experiencing the impacts of a tropical storm or hurricane every year. As seen with Hurricane Sandy’s flooding of Chelsea galleries in New York in 2012, storms not only produce casualties and damage buildings, but can destroy unique works of art. Florida’s art collectors worked hard to prepare for hurricanes. Damien Hirst's “Gone But Not Forgotten” at the Faena Hotel Miami Beach was secured thanks to extra layer of protection against wind and debris.

Photograph: Damien Hirst, “Gone But Not Forgotten” (2014), image via Faena Hotel Miami Beach

Museums made efforts as well. For instance, at the Pérez Art Museum in Miami, just off Biscayne Bay, an emergency crew of 14 security, operations and engineering staff members began staying overnight in the museum to protect its valuable collection. Every spring at the Perez Museum, policies and procedures are checked and improved and training is implemented so that staff could cope with for the hurricane season, but the museum's strategy to adapt to climate change and mitigate its effects is much more articulated. In 2013, the Pérez Art Museum of Miami opened its new $131 million building, designed by Herzog & de Meuron, right on the Miami shoreline. Architects responded with an innovative design at the challenge of withstanding a Category 5 hurricane and addressing the risk of sea level rise. This project developed an integrated approach to water, transportion and ecosystem management, a true example of a multidisciplinary team driving sustainable design for resiliency (the building is LEED Gold Certified).

Photograph: The Perez Art Museum in Miami, image released in CC

At the Perez Art Museum the management of water, whether rain, sea or condensation, became the key feature that informed almost every other decision. Air conditioning and irrigation is provided by the building itself through high trellised structures that shade the decks, and convey sea breezes and water to make the subtropical exterior setting comfortable for people and plants. The sustainable design of the building is associated to the metaphor of a forest of mangroves with its flexibility and porosity to air, light, water and ecological functions. The structure is made of stilts and horizontal layers ending with a light-filtering canopy. The trellis on the roof is made of slats that are more open to the north and more dense to the south, in order to allow better light control where the galleries are located. Museums are renowned to be highly energy consumptive because of their narrowed climate control for preservation. Because of this, specific attention was given to the HVAC system, positioning ducts under the floor allowing a better optimization of indoor air flows. The use of concrete was minimised through the use of the Cobiax System, a constructive method that involves recycled plastic domes as voids where concrete is not needed for a structural reason. The first floor is elevated 5.50 meters above the high-water mark left by Hurricane Andrew in 1992 (Category 5), acting as a cushion from potential effects of climate change. Majestic entrance doors are made of teak, with a multi-prong pin system that lock the doors in several places to secure them against Category 5 hurricane winds. Windows are the largest hurricane-resistant panes ever installed in US.

In cases of extreme rain, storm surge or flooding, an innovative porous-floored garage, paths and rain gardens at the Museum capture water, funneling it into the ground, reducing local flooding and runoff. In case of flood, a power generator on the third floor of the museum ensures electricity to the building even if lower floors are affected by water. It has an autonomy of three days and can be refueled by track or, if roads are blocked, by boat. Even the system of hanging gardens created by French botanist Patrick Blanc are billed as Category 5 hurricane resistant. Plants can easily be replaced if needed, and the fiberglass tubes used to hang them are reinforced with stainless steel armatures so that the mechanical system and irrigation system remain intact. The art storage space is located 45 meters above sea level to ensure security from flooding and water damage. It has a HVAC system specifically designed to handle humidity levels that might follow a storm event. Outside sculptures are ensured to resist to hurricanes up to category 5 or have special protocols to be de-installed. But this sense of responsibility goes beyond the museum building and collection and reach its community.

Among the initiatives in the Hurricane Irma aftermath, in order to relieve some of the stress from Hurricane, the Museum invited South Florida residents to enjoy a day at the museum with free admission, and hosted a variety of activities, including family-friendly art-making and an evening happy hour. Then, with the aim of raising awareness of Irma and Maria's devastating effects across the Caribbean and U.S., and the urgent need for basic necessities, the museum in a partnership with the Caribbean Film Festival and The Miami Foundation, launched an initiative which encouraged residents to bring select items to the Museum’s reception desk and receive free admission during regular museum hours.

Miami has been deemed the ground zero of climate change. For this reason many art galleries and cultural organizations have developed many different art and climate related initiatives. The Bass Museum of Art took these issues very seriously. The Museum closed in 2015 and reopened at the end of 2017, after a $12 million renovation led by architects Arata Isozaki and David Gauld. According to the museum’s executive director, Silvia Karman Cubiñá, the first priority is to ensure all the staff and community are prepared for extremes in order to be safe during and after the storm (Cascone and Goldstein, 2017). But the museum's strategy to raise awareness about climate related issues goes far beyond their organization. The Bass launched a ten-year initiative to grow its international collection. The initiative was celebrated with the third acquisition last August, “Petrified Petrol Pump (Pemex II)” a work of the US-Cuban duo Allora & Calzadilla. Analogously, one of the works under consideration for aquision was a water sculpture by acclaimed artist Jeppe Hein. But it was passed over as a permanent exhibit because it could not efficiently recycle water as required by the Miami Beach's code. This choice reflects the balance between the museum's mission, its ethical imperatives and the knowledge that creates through its collection.

Photograph: Allora & Calzadilla, “Petrified Petrol Pump (Pemex II)” (2011), black lava and travertine stone, 100 x 80 x 80 inches; , Allora & Calzadilla/ Kurimanzutto, Mexico City.

Climate change is a complex topic which presents the challenge to consider a multitude of data and phenomena only apparently unrelated. In order to navigate in such a multilayered landscape, museums need to tell stories through text, images, media and objects which can be combined to weave a comprehensive narrative. “EXIT”[1], a Paul Virilio's dynamic cartography realised by a multidisciplinary group led by Diller-Scofidio and Renfro, provides an excellent example. The work was commissioned by the Cartier Foundation in 2008 for the exhibition Native Land, Stop Eject and then successfully displayed in several places included Paris and Copenhagen during the United Nations Climate Change Conferences but also Melbourne, Bilbao and Valparaiso. “EXIT” is an immersive environment of continuiously updating, animated maps which aims for an emotional effect through a dynamic representation of facts, showing connections and evolution through time.

This combination of data gives a comprehensive understanding about the correlation of many aspects of climate change such as global poverty and natural disasters. Climate change is about social justice and Museums, as trusted independent institutions, have the potential to be relevant, socially-engaged spaces in our communities, and act as agents of positive change. To do that, Museums need to embrace a broader view. It is not about to create new knowledge or advocate solutions; it is something much deeper and more subtle – “to look at the future of our community and make us reflect and rethink what it is to be a human being in the 21st century” (Janes, 2015).

Driving forces are both outside and inside the Museum environment and ask Museums to move towards a more responsible approach in their organization and management. Within this framework over the few years, different grassroots groups have provoked a critical and creative debate around museum sponsorships from oil companies that threaten the credibility of important institutions and eroded the public trust. Campaigners obtained several victories and the recognition by several museums that museum environmental ethics goes beyond carbon footprints and materials.

Photograph: Amy Scaife/Liberate Tate

The challenge is to create a narrative “committed to build sustainable communities beyond the outmoded economy of industrial growth and unbridled consumption” (Korten, 2014) or, using the words of Jennifer Newell: “perhaps the challenge now facing museums, as the traumatic consequences of rapid, erratic changes in climate patterns begin to unfold, is to enable storytelling that constructs meanings that are themselves more powerful than the most ferocious storms, devastating fires, churning floods, and bitter droughts.” (Newell, 2017).

About the author

Ferdinando Adorno is an Italian architect, trainer and consultant for the tourist and cultural sector with Yo Soy Hospitality. He’s been teaching assistant in Exhibition Design and PhD Candidate on Green and Sustainable Museums at the University of Florence, Italy. He’s experienced in International context with a strong belief that culture, in the long term, has a key role in building more fair and environmentally responsible communities.

References

Kennicott P., With the planet in peril, arts groups can no longer afford the Koch brothers’ money, The Washington Post, June 5, 2017.

(Accessed April 10, 2018)

Adger N. et al., Cultural dimensions of climate change impacts and adaptation, Nature Climate Change; volume 3, pages 112–117; 2013

Cascone S. and C. Goldstein, As Hurricane Irma Moves Toward Florida, Museums Shutter Up and Prepare for the Worst; Artnet News, September 7, 2017. Available at: https://news.artnet.com/art-world/art-museums-hurricane-irma-florida-1073123

(Accessed April 10, 2018)

Janes, R.R., The End of Neutrality: A Modest Manifesto, Informal Learning Review; n.135, November – December, 2015. Available at: https://coalitionofmuseumsforclimatejustice.files.wordpress.com/2017/08/the-end-of-neutrality-ilr-article-dec-2015.pdf

(Accessed April 12, 2018)

Korten, D., “Change the Story, Change the Future: A Living Economy for a Living Earth.” Presentation at the Praxis Peace Institute Conference, San Francisco, California, October 7, 2014. Available at: http://livingeconomiesforum.org/sites/files/pdfs/David%20Korten%20Praxis...

Newell J., Robin L., Wehner K., eds. Curating the Future: Museums, Communities and Climate Change. Abingdon: Routledge; 2017.

Add new comment