By Susan Spero

Last week (June 16, 2014) the White House held its first ever Maker Faire, an effort that at least for me, signals a coming of age of the Maker/Tinkering movement within the United States. From the earliest beginnings of Maker Faires, museums have partnered to create, design, and engage audiences with these events. The Exploratorium played a strong role during the Maker Faire inaugural event in 2006 in Silicon Valley; two additional museums—the New York Hall of Science in the East and The Henry Ford near Detroit—now hold respective “flagship” Faires on their grounds. In fact you might not know that your institution can partner with parent organization Maker Media to create your own Maker Faires.

Variations of the hacked The Art of Tinkering book showcased at the Exploratorium in San Francisco. (photo by S. Spero).

While do-it-yourself exploration has been present for a long time in museums, more recently several institutions have dedicated significant space for maker-style activities. In 2013 the Exploratorium opened its new site with more floor space committed to its Tinkering Studio. Likewise, in June 2014 the New York Hall of Science debuted its new Design Lab. To go along with the White House Maker Faire, the Institute of Museums and Library Services released these talking points (pdf) about Museums, Libraries and Maker Spaces. Museum work and the Maker movement readily go hand-in-hand; its increasing popularity allows doing and visitor participation to take center stage.

If you haven’t yet rubbed hands with the Maker movement, there are several resources about making, tinkering, and learning. I offer three to start.

The Art of Tinkering (Weldon Owen; First Edition [February 4, 2014]) is a joyful read wherein you meet playful artists, tinkerers, and their work. Authors Karen Wilkinson and Mike Petrich are the co-directors of the Tinkering Studio at the Exploratorium and have assembled a staff of tinkerers who not only at times tinker with physical material, but also have spent years together tinkering with this hands-on approach. You meet their tinkering spirit the minute you crack open the book: “Hack this book,” commands the opening line. Sure enough, readers can hack this book by completing circuits on the front cover, which has been printed using conductive ink. Add your own power source to make it blink with light, beep with sound, or whatever your mind can imagine.

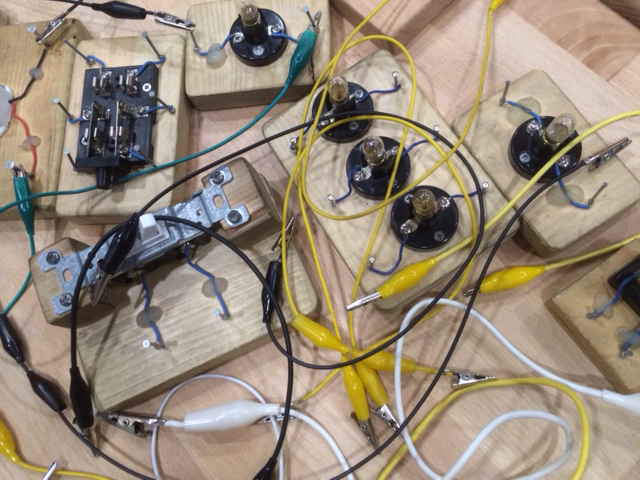

Tools for playing with circuitry in the Tinkering Studio

In their opening essay, Wilkinson and Petrich offer a sense of what tinkering is, “..in our minds [tinkering] is more of a perspective…It's fooling around with phenomena, tools and materials. It’s thinking with your hands and learning through doing. It’s slowing down and getting curious about the mechanics and mysteries of everyday stuff around you. It’s whimsical, enjoyable and ultimately about inquiry.” They go on to say more in the text, and their extensive experience shines through the entire book.

The book offers fifteen guiding principles of tinkering that in and of themselves make it worth a read. These include such notions as: Merge Science, Art and Technology; Create Rather than Consume; Revisit & Iterate On Your Ideas; and one of my truism favorites: Take your work seriously without taking yourself seriously.

The book is both a how-to guide and a collection of dozens of artistic/tinkering approaches seen through the photographs of studio spaces, tools necessary, and the end-results. Throughout the story, readers explore the tinkering mind-sets and methods that have been developed and refined over time, frequently after artists worked with the Tinkering Studio. Reviewing these varied approaches to making should inspire you to find makers within your own community and encourage them to work with visitors on your own museum floors. And if you have no interest in tinkering, consider the book as a great introduction and tribute to tinkering itself.

A second resource for learning more about Maker concepts is an anthology of voices gathered around the key ideas suggested in the title: Design, Make, Play: Growing the Next Generation of STEM Innovators (Routledge [March 15, 2013]). Margaret Honey and David E. Kanter, both from the New York Hall of Science, edited this book, which includes articles by established leaders of the Maker community. Several of the texts focus on how the Maker movement connects to STEM (Science Technology, Engineering and Math). For those in the art world, the ideas within these chapters apply equally well to STEM’s morphing corollary, STEAM, an acronym that adds an A for Art into the mix.

Authors offer insight into creating Maker spaces and activities on the museum floor, such as describing the evolution of the classic Maker activity “Squishy Circuits.” Games, block parties, and puzzle-solving technology demonstrate the wide range of experiences welcomed within this playful and problem-solving arena. Combined together, the articles strongly advocate that play and fun through making encourage exploration and discovery. Authors in all case studies explain the reasoning behind Maker activities, offering rationales that can be cited when arguing for your own Maker project.

If you need a summer read try Frank R. Wilson’s thought provoking The Hand: How Its Use Shapes the Brain, Language, and Human Culture, and the oldest of my suggestions having been published in 1999. This third resource is a well-written, non-fiction book about the capabilities of our hands. The book’s subtitle accurately emphasizes the whole point of the book: Wilson’s claim that we learn about our world not only by using our brain, but also through the partnership of our brains and hands. Making is deeply dependent upon how we use our hands, so the more we can learn about them the better. Wilson’s book is a great guide.

Wilson spent his career as a neurologist who often worked with professional musicians suffering from hand ailments. He presents a well-told and scientifically fascinating story of the hand from multiple perspectives—from the academic anthropologist and physiologist to the performing puppeteers, musicians and even magicians. It is a dizzying array of views on a part of our body that most of us use daily, generally without thinking.

The connection of this hand tale to the Maker movement seems direct as you read through the book, especially the notion that our hands are one of the keys to understanding the world. After reading this book I have a better sense of how the hand works and how its behavior lets me learn. The challenge is to set up compelling making and tinkering events that ask us to use our hands in both recognized and new ways.

Before ending I must acknowledge the incredible irony that this post on making is dedicated to resources you read to learn lessons about this movement. My hope is that perhaps by reading about successful Maker models, you can pick up the spirit of the Maker movement. With enough inspiration you can then use the ideas and approaches to construct a program within your own institution. Nonetheless, I do realize that the best way to get the power of the Maker movement is to actually go to a good Maker Faire and use your hands to learn. Reading is good, but not enough. Find a Maker Faire near you, and go—then read the books!

Susan B. Spero, Ph.D. teaches Museum Studies at the John F. Kennedy University. Two years ago she was fortunate to spend time with the Exploratorium’s Tinkering Studio Team during a multi-day workshop with the Arkansas Discovery Network. The experience was enough to revive her long-lost tinkering tendencies, and she has returned to playing with materials for their own sake.

Add new comment